Natural Medicine

- WSP Rhodes

- Jun 8, 2025

- 14 min read

Forgive my hiatus, I have been dealing with some personal issues.

When you think of ‘natural medicine’ or plant-based medicine,’ you almost certainly think of different types of herbal or alternative medicine and pseudoscience. And this is a well-earned reputation; pre-modern medicines have been co-opted by pseudoscientists in order to sell an ideology as well as ‘medicines’ of dubious effectiveness. All that being said, the story of these pre-modern remedies is a tad more nuanced than what one may imagine from my blanket dismissal. Many of these remedies have an interesting story within the history of medicine. Plant-based medicines and molecules continue to have a role in modern pharmaceutical science. Again, I want to reiterate that I’m not giving support to alternative medicine; I would advise heavily to only take pharmaceuticals prescribed and recommended by a licensed medical professional. But by digging into the questions that arise from this recommendation, you find a lot of interesting information about modern drug discovery, the history of science, and even some theory of knowledge.

History of Medicine

For this section, let’s agree on some definitions. When I use the term ‘modern medicine,’ I am referring to drugs and medical practices developed using modern scientific techniques. That is to say, when a particular substance or practice is suspected to have therapeutic effects or a particular model of how a part of the body works is proposed, scientists will design an experiment that will make it as obvious as possible if their hypothesis is correct or not. Their original hypothesis, the design of their experiment, and all of the results are then painstakingly written out and published so that other scientists can learn the results, critique the experimental design, or incorporate the new information into their own experiments and models. The scientific method is perhaps the most effective mechanism for refining and building up societal knowledge, but it has only existed in this mature form for about 400 years. So for ‘traditional’ medical methods that predate this system, I’m going to use the term ‘pre-modern medicine’ as a comprehensive term.

Since ancient societies had very little interaction between each other compared to modern times, there are as many distinct ancient medical traditions as there are ancient societies. That said, it is believed these traditions developed in similar ways across all such societies. Prehistoric hunter-gatherers would regularly come across plants they were unfamiliar with and had to find safe ways to tell if they were poisonous or not. These techniques likely resembled something like the US Army’s Universal Edibility Test*, followed by careful memorization of the results by at least one person in the group or tribe. This would inevitably mean learning what affects certain plants had on the body (pain relief, stimulant/depressant effects, etc), which would also be memorized so they could be used to manipulate the body in useful ways. While this wasn’t formalized like the modern scientific method, this was a form of experimentation and recording the results. This lack of rigor meant it would’ve taken far longer to develop a complex medical tradition, but there are prehistoric human remains dated to be at least 65,000 years old with evidence of known medicinal herbs in their diets, so prehistoric medical practitioners had a long time to build up and refine their pharmaceutical knowledge. The knowledge of what plant species were medicinal, where to find them, and how to prepare them would’ve been passed down by oral tradition by medical practitioners (shamans, medicine men, etc), but would also have been written down once writing was invented. We also have fossil evidence of surgical procedures done as early as 10,000 years ago (likely as a last resort) and ancient medical texts dictating healthy diets and lifestyle in several cultures, both of which were probably developed through similar trial and error. But getting back to pharmaceuticals, modern studies have been done on commonly used herbal medicines and found that many of them are at least somewhat effective at treating the ailments they’re commonly used for. For a small sample, here’s a study looking into the effectiveness of the ten most commonly used herbal medicines in the United States. This study found that half of the herbs were likely somewhat effective, albeit with side effects that made them poor substitutes for their modern equivalents. While these remedies are inferior to modern medicine, their effectiveness is evidence that premodern peoples were developing useful knowledge with the tools they had available to them.

So, why did only half of these herbal remedies work? While our ancestors weren’t less intelligent than us, they were working with a lot less information and resources than we have today. Modern scientific studies are done with a lot more rigor to ensure the knowledge acquired is accurate and useful, which I will go into in more detail later. Also, since much of this pharmaceutical knowledge was passed down orally, a lot of details about how the knowledge was initially developed would have been lost over time. There are several pre-modern medical techniques (e.g. acupuncture) where we can’t tell how the technique was originally developed, making it harder to determine its effectiveness. This also likely contributed to an attitude of authority from tradition amongst pre-modern medical practitioners; since you can’t ask your mentor why a certain remedy works, it’s much harder to question their authority. This stands in contrast to modern science where all research is laboriously catalogued and researchers must earn their authority through the effectiveness of their work. Additionally, pre-modern medicine was hampered by the fact that the only aspects of illness that could be observed were those that were visible to the human senses. You’ll notice that all herbal remedies and pre-modern therapies were exclusively symptom management. Not only would this mean that diseases could rarely be outright cured, but it also meant there was very little means of researching the causes of disease itself. Multiple pre-modern medical traditions had theories for how the body worked or what caused disease, but those models had to be logically deduced from very limited information. This meant these models were often woefully inaccurate as they were built on logical deductions made from limited information with reasoning that appealed to the human mind even when such wouldn’t be applicable.

To give you a case study, let’s look at perhaps the most famous example of pre-modern medicine to a Western audience; humorism. This model of illness, developed by Hippocrates of Kos around 400 BCE, posited that there were four important bodily fluids (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile**) and that illness is caused by these four humors not being in balance with each other. Each humor was associated with one of the four classical elements (earth, air, fire, and water), as well as one of the four seasons and stages of life, with each element-humor pair being either hot or cold and either wet or dry (blood and air are hot and wet, phlegm and water are cold and wet, etc). Diseases were then associated with an element, time of year, or a temperature/moisture level to deduce what humoral imbalance caused it, just as diets and herbal remedies were associated with elements and temperature/moisture levels to serve as counterbalances. Diseases*** could be caused by anything that unbalances the humors, such as poor diet, weather, and numerous aspects of lifestyle. Books were written listing all the herbs and foods that could rebalance the humors, along with changes in diet and purging excess humors in extreme cases. For example, fevers are a ‘hot’ disease, so they’d be treated with foods or medicines associated with ‘cold’ humors and elements (such as chamomile, cucumbers, and lettuces), or by bloodletting in severe cases (removing a ‘hot’ humor). Hippocrates and his successors developed this model by observing disease symptoms in patients and then deducing the commonalities between them. It’s likely the idea originated from their observations of their patient’s secretions and effluvia with the assumption that their bodies were purging excess humors (i.e. blood in your vomit means there’s too much blood in you). From there, it was a lot of logical deduction based on the associations stated above. Here’s a video by Patrick Kelly if you want more detail.

I’m sure you’ve noticed many of the fallacies that were made when developing this model. While Hippocrates and his successors put a lot of work into finding commonalities between ailments, he could only deduce commonalities based on a premodern understanding of the world. Therefore, he associated the four humors (aka the four colors of fluids the body secreted) with other culturally significant groups of four in the natural world, i.e. the elements and seasons. These associations were built upon with more logical deduction, but these deductions were based on what the human mind found understandable, not how the human body actually worked. Diseases and cures had to be made to fit the model’s logic even if the reasoning was flimsy, i.e. leafy greens were associated with the element air (and thus good for treating diseases caused by too much black bile) because they were light and fluffy. So, why did this clearly incorrect model of health survive for so long? A big reason was that the model was developed by Hippocrates, who’s been credited with establishing medicine as a distinct profession in the Greek world and made numerous legitimate advancements in multiple aspects of medicine, including surgery, urology, orthopedics, mental health, prognosis, disease categorization, methodology, and medical ethics (hence the Hippocratic Oath). Also, being a rational, all-encompassing model of health and the body made it appealing, especially to doctors and rationalists. The mere idea that disease was caused by rational, identifiable causes that could be treated mechanistically was fairly revolutionary (most in Hellenistic Greece attributed sickness to divine will), and this worldview made medicine as we would know it possible. Academics from Roman, Islamic, and Medieval Christian traditions studied humorism and built upon it with their own medical research. While many of these academics were critical of humorism and found flaws with it, these critiques couldn’t really disprove a theory this foundational to the field since there were no better theories to take its place and there were no concerted effort by scholars working together to find alternative explanations. It was between the 1500s and 1800s that the idea slowly began to die out as new scientific advances (the microscope, the legalization of autopsies, etc) led to new understandings of the body that started to poke holes in humorism. Parts of humorist theory would survive for a few more centuries wherever there weren’t better theories of how the body worked, but the slow development of new theories of medicine, such as germ theory, slowly outcompeted humorism as a means to explain disease.

Modern Medicine

A lot has changed between then and now, especially in how research is done. Today, if a particular compound was believed to be of pharmaceutical benefit (more on how we figure that out in a minute), the procedure is much more detailed. Like in premodern times, this potential pharmaceutical would be given to a volunteer and their response carefully measured and recorded. Unlike in premodern times, the number of volunteers would be far greater. I’ve talked about the size of clinical trials before, but modern phase 3 trials can have up to 3,000 participants in order to gauge how a drug interacts with a diverse group of people and to confirm its effects aren’t coincidental. Half these participants would be assigned to a control group, given a fake version of the drug so as to have a reference point to compare the drug’s effects to. Neither the participants or the experimenters would know who exactly is receiving the drug or the placebo to ensure no one can subtly influence the results. Both groups would be administered their respective meds in identical environments, potentially being kept in identical environments for an extended period of time and with extensive medical backgrounds taken to weed out anyone with an atypical body. All the plans for this experiment would be written out and approved by medical boards beforehand to ensure that there are no potential flaws with the experiment that could skew the data (as well as to ensure the experiment is done ethically). Standardized experimental designs are often used (such as the four phase trial model) since they’re known to work well and to reduce variability between experiments. During the experiment, relevant vital signs are measured consistently, both for experimental data and to identify any side effects early. Once the data is collected, statistics are done to ensure any observed effects are being caused by the drug itself and are not a coincidence. Finally, all of this data, experimental design, and results are published in scientific journals that can be read by anyone, particularly those in the same field. Other scientists will notice any flaws in the experiments or results and can perform similar experiments to build on this knowledge. This is the amount of effort and infrastructure it takes to make modern medicine as trustworthy as it is. Premodern tribal groups were on average smaller than 3,000 people, with few if any having the freetime for months-long medical trials. Without modern medical equipment, the only data that could be collected would be what the participants report and what was visible on their bodies. If a society didn’t have written language, recording this data and capturing all these precise details of experimental design would have been untenable. And while there were ancient societies who studied and shared medical texts and the results of experiments, these studies couldn’t travel much farther than their own region in a single human lifetime. It takes a very complex society to create the tools necessary to study something as complex as the human body, which is why medicine has only become as reliable as it is relatively recently.

But just because our methods of developing medicines have advanced doesn’t mean we’ve abandoned all of our old knowledge. For example, many cultures would use the bark of willow trees (either chewed or as a tea) to relieve pain and reduce inflammation. The specific chemical in willow bark that caused this effect is salicylic acid, which is today the active ingredient in aspirin. A common treatment for malaria and certain parasitic diseases today is artemisinin, a molecule found in sweet wormwood which has been used as a malaria treatment in traditional Chinese medicine. The drug digoxin is used to treat heart conditions, both today as a pill and in the past as the plant foxglove. Opioids from codeine to morphine were initially identified and derived from poppies. I could go on, and these are just examples where the primary purpose of the modern drug is the same as the traditional use (i.e. Madagascar periwinkle being used in the past to treat diabetes and as a chemotherapy today). Now, the modern forms of these drugs don’t necessarily come from these plants; these molecules can be synthesized from other compounds in a laboratory or extracted from other biological sources, whichever is most efficient. And I would personally advise you to use the modern pill form of these drugs instead of as an herbal supplement, as pills will have a consistent, more concentrated amount of the active ingredient, will have no other substances that could trigger side effects, and their contents are regulated by modern health agencies. But this shows how many of these older remedies can prove themselves by modern standards, and they become modern medicines when they do.

Finally, I’d like to talk about the role of natural products in modern drug discovery. The most common way new drugs are developed today starts with the identification of a particular protein or molecule that is directly linked to a disease, say a protein on the surface of a cell that makes it easier for a virus to get inside. Once we know changing this protein will cause a desired effect for the patient, it gets screened against an enormous library of small molecules one at a time to observe how the protein interacts with each molecule. If any of these molecules are observed to bind strongly to the protein and make it do what we want, scientists can begin testing these molecules for their efficacy and safety as a drug, ultimately ending in clinical trials like we described before. The problem with this method is that these libraries of small molecules can be absolutely massive, the largest of which containing billions of molecules that each have to be tested against the protein in question. High-throughput screening methods are used to speed this process up, from advanced robotics to quickly perform the screenings to advanced computer simulations that could potentially perform the screening process virtually. But for drug discovery to be practical, scientists need to find ways to narrow down their search. This is why there are many modern drugs derived from traditional medicines; if you’re looking for compounds that can relieve pain, traditional pain relieving remedies are a good place to at least start looking. And repackaging traditional remedies**** is just a small portion of modern plant-based medicine.

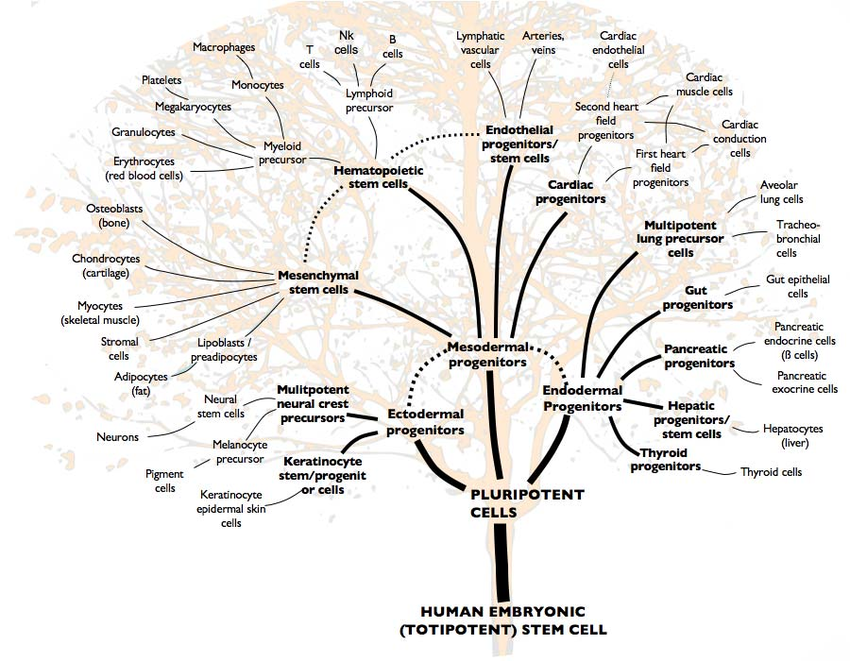

Today, roughly 40% of medicines are derived from plant-based compounds, with the majority of these drugs coming from some form of bioprospecting. Bioprospecting is the process of exploring and sampling unique compounds and macromolecules from plants, fungi, and microorganisms to find commercially useful products such as pharmaceuticals. Samples of everything from common plants to unique bacteria in isolated environments are collected from nature, their DNA and proteins are sequenced, and these molecules are added to the libraries used for high-throughput screening. While useful compounds can be found anywhere, understanding what a compound is used for in nature can lead to productive uses for humans. For example, all anti-cancer chemotherapies work by somehow inhibiting cell reproduction; cancer cells reproduce far faster than healthy cells, so such a drug will disproportionately affect cancer cells. Since plants can’t run away from predators, they frequently develop poisons to prevent predation and parasitism, and preventing cellular reproduction is a very effective mechanism of attack for a poison. If bioprospectors know a plant species uses such a mechanism, they can screen through that species’ molecules to determine if they would be useful for human cancer treatments. Examples of plants used to make modern chemotherapy drugs include Madagascar periwinkle, Pacific yew trees, American mandrakes, Chinese happy trees, and many more with more under investigation. These plants can be farmed specifically to make drugs, genetic engineering can be used to create yeast or bacteria with the genes to make the anti-cancer compounds, or the molecules can be synthesized through entirely inorganic chemical processes, whichever is most effective or least expensive.

I want to reiterate again; I am in no way advocating for alternative medicine with this post. Not every traditional medicine has been found to be effective, and the ones that have been found effective have been incorporated into modern drugs that have the benefit of modern drug manufacturing and regulation to make them more effective and less toxic. The only real defense I can give for traditional systems of medicine in the modern day are their use in rural regions of developing nations, where modern pharmaceuticals and medical practitioners aren’t common and one has to use what’s available. In the United States, herbal remedies are less likely to come directly from traditional medical practices and more likely to come from the million-dollar supplement industry, which has far less regulatory oversight than ‘mainstream’ medicine. If someone in a developed nation tries to convince you that a vitamin supplement can cure whatever ails you, they either want to erode your trust in experts so you will have no one to trust but them, or they’re trying to sell you vitamin supplements. And it’s a shame that so many of these traditional medical practices have been appropriated by charlatans, because they can serve as a fascinating glimpse into the history of medicine and how knowledge is formed. So I hope you’ve found this topic as interesting as I have.

For More Details

*Since the Universal Edibility Test was created for modern people in survival settings, I feel it’s important to note that the UET is considered controversial amongst survival experts as it is decidedly not foolproof, as certain plants and fungi are poisonous enough to be lethal even at incredibly small doses. I include it here because it gives an accurate sense of how prehistoric humans would have gauged the toxicity of food, but please don’t take survival advice from anything I write.

**Yellow bile is likely the bile secreted by the gallbladder, but black bile is probably the mixture of blood and tissue that leaks out of the liver or kidneys when they’re cut into. Again, Hippocrates had no access to scientific instruments other than the human senses, so he had no way to tell what his humors were chemically other than their appearance. The four humors are basically just the roughly four colors that human secretions tend to be (red, yellow, black, and clear) that physicians assumed were each discrete, unique substances.

*** To be clear, there was no understanding of the underlying cause of diseases because the only underlying cause was humor imbalance. To humorists, diseases didn’t cause symptoms, the symptoms were the disease.

**** This didn’t really fit in the main text, but I think it’s worth talking about. One of the controversies of deriving modern pharmaceuticals from traditional medicines is that the pharmaceutical companies making these drugs will often try to patent or copyright them despite the drug being derived from the knowledge of indigenous groups. The indigenous groups are rarely provided fair compensation and are sometimes legally locked out of their own practices. This practice has become known as biopiracy and work is ongoing in international intellectual property law to prevent this new form of harm.

Comments